I realise I have always carried a quiet hierarchy of disciplines, one that shaped how I understood “smartness”:

Maths / Physics → Medicine → Applied Sciences → Humanities → Arts

I don’t think I was unique in this; it likely mirrors how many of us are taught to value knowledge from a young age.

For a long time, I felt secure near the “top.” I studied biomedical science, worked in a genetics lab, ran experiments, and felt that I “contributed meaningfully” to science. This construction of a discipline hierarchy probably began in my school years. Growing up, I excelled in the sciences and was encouraged to pursue them. At the same time, I also loved English Literature and History, even choosing to study them at A-level alongside Chemistry and Biology. As I stressed (and cried) preparing for my science exams, I remember thinking I would have loved to do a degree in English Literature, but I feared it wouldn’t be enough. I wouldn’t be “smart enough,” and it wouldn’t lead to a good job. I had internalised the hierarchy so thoroughly that following my passions didn’t even seem an option.

I chose a degree in Biomedical Sciences, but over time I drifted – first towards mixed methods, then qualitative methods, and finally embracing the social sciences. With each step, I questioned myself: Was I abandoning rigour? Leaving “serious science” behind? Was I less capable for doing so?

Then I read Ruth Hubbard’s The Politics of Women’s Biology, and it was like reading about myself. Hubbard writes:

“It is difficult for feminists who, as women, are just gaining a toehold in science to try and make fundamental changes in the way scientists perceive science and do it. For this reason many of us scientists who are feminists live double lives and conform to the pretenses of an apolitical, value-free, meritocratic science in our working lives while we live our politics elsewhere. Meanwhile, many of us who want to integrate our politics with our work analyse and critique the standard science but no longer do it.”

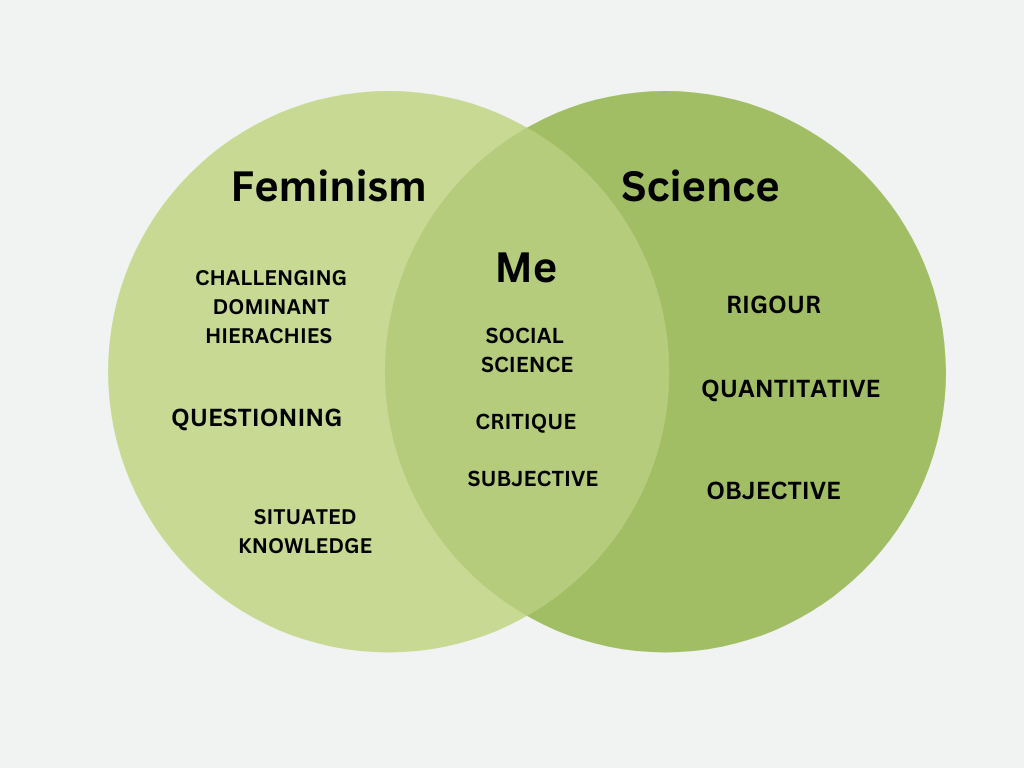

I resonate deeply with this. Coming from a life sciences background, I now find myself situated in medical sociology. I feel the tension of those “double lives”: the part of me trained to value lab work, objective measurement, and conventional science, and the part pursuing questions that require reflection, critique, and a feminist lens.

Even now, I still identify as a “Woman in STEM,” but I feel conflicted about whether I can truly claim that label. The hierarchies I’ve internalised tell me I’ve moved too far “down the ladder,” even though I feel just as invested in science as ever. Academia constructs these hierarchies subtly but persistently, and they become particularly visible at interdisciplinary conferences and other events. You can see it in how people talk about methods, present work, or subtly rank the “seriousness” of different fields. At my first interdisciplinary conference, I quietly downplayed my research. “It’s not as data-heavy as others’ work,” I said. “It’s just qualitative methods”. The words tasted like self-betrayal, and I realised how deeply I had internalised the hierarchy.

Reading Hubbard helped me see that moving into social sciences and qualitative work wasn’t a failure, a softening, or a step down. It was necessary —a search for ways of knowing that the traditional hierarchies couldn’t offer. My self-diminishing habits weren’t personal failings, but symptoms of a broader system of values I, like many others, had absorbed.

Academia may construct hierarchies, but I am learning to carve space in the in-between: for the scientist who values experiments and data, for the scholar who values reflection and critique, and for the feminist who refuses to shrink to fit. Women, early-career researchers, and interdisciplinary scholars often feel these pressures acutely. We internalise messages about what counts as “serious” work, which can make us diminish our own contributions or hesitate to pursue the questions that matter.

Recognising these hierarchies is the first step toward change. When we see that no single discipline holds a monopoly on rigour, we can expand what counts as meaningful research, collaboration, and impact. Doing so doesn’t just liberate our work; it opens space for others to inhabit the in-between, the intersections, and the unconventional paths that academia too often undervalues.

Claiming that space means noticing when I slip into old habits: apologising for my work, softening its significance, or comparing it to others in ways that feel reductive. It means acknowledging the hierarchy I carried for so long while actively resisting its hold on how I value myself and others. The double lives Hubbard describes aren’t unique—they are part of a broader structural and cultural pattern.

Ultimately, being a feminist in the sciences is about embracing contradictions, living with tension, and refusing to let hierarchical judgments define what counts. It is about moving forward with curiosity, integrity, and critical engagement, even when the field, or our own internalised beliefs, whispers that we don’t belong.

I am still learning, still negotiating, what it means to claim my work confidently, and I’m still figuring out how to inhabit multiple identities as scientist, scholar, and feminist. But with each step, I feel more certain that the boundaries imposed by disciplinary hierarchies can be pushed, bent, and redrawn. And that realisation – that I can belong in the in-between – allows for possibility and academic freedom.